A Study on the Performance of the Root Name Servers

Kenjiro Cho, Akira Kato, Yutaka Nakamura, Ryuji Somegawa

Yuji Sekiya, Tatsuya Jinmei, Shigeya Suzuki, and Jun Murai

WIDE Project

{kjc,kato,yutaka-n,somegawa,sekiya,jinmei,shigeya,jun}@wide.ad.jp

Abstract

This is an ongoing effort to investigate the root name server

performance from various locations of the Internet.

We use simple probe programs to measure the responsetime of the root

servers. We also measure the response time of the ccTLD servers to

compare them with the root servers.

Introduction

One of the most critical components of the Internet is the Domain Name

System (DNS) [MD88]

that translates host names to and from IP addresses.

DNS is a distributed database in which domain names are maintained in

a hierarchical tree structure.

A domain in the domain name space may be divided into subdomains,

and the administration of a subdomain may be delegated.

A zone is an administrative unit of the domain name space in which a set

of name servers are authoritative for the domain as well as

responsible for providing referrals of its delegated subdomains.

Crucial to the operation of DNS is the root name servers that

provide referrals to authoritative name servers for the top-level domains.

Currently, there are 13 root name servers; 6 in the East Coast, 4 in

the West Coast, 2 in Europe, and 1 in Japan

(root-servers.org,

a map at WIA).

The number, location and distribution of root name servers

affect the total system performance and reliability of DNS.

It is advantageous to have a root name server nearby

but there is not enough data to technically investigate better root

server distribution for the common good.

The goal of this project is to provide technical methods to evaluate

locations of root name servers

in order to better understand the performance of the root name server

system and to plan for future reconfigurations.

Another goal is to provide recommendations on server selection

algorithms and cache mechanisms for recursive name servers at the

client side to make good use of the root servers.

Note that this study addresses only the performance aspect.

We do not discuss other important operational or political factors

such as robustness and reliability.

Our approach is three-fold:

- Measurement:

Make root server performance measurements from many sites

around the Internet.

We are interested in how the root server performance looks

from different parts of the Internet, especially, from sites

far from the core of the Internet.

- Analysis:

Study the server selection algorithms and the cache behaviour

of name server implementations so as to determine whether

good algorithms mitigate the need for good root performance.

When the name cache mechanism works as designed,

the number of queries to the root name servers should be very

small for each recursive name server at the client side.

If the impact of the root name server performance to the

entire DNS performance is negligible, it is better to drop

performance concerns and focus on reliability issues.

- Simulation:

Use data from 1 and models from 2 in simulations of changes to

location of the root servers.

Once we have measurement data from various locations,

it becomes possible to simulate rearrangement plans.

Measurement

Method

Two simple programs, rootprobe and cctldprobe, were developed.

rootprobe sends queries to the root servers every 5 minutes,

and reports the measured response time by e-mail.

cctldprobe is a ccTLD version of rootprobe, and sends queries

to the ccTLD servers instead of the root servers. The query interval

of cctldprobe is 2 hours.

Both programs exit after running for 2 weeks.

The latest version of the software:

rootprobe.tar.gz,

README.

Measurement Results

The results are available from

here, and updated once a day.

For each measurement site, 3 graphs are created.

The first graph shows the response time and the query loss rate for

each root server.

The second graph is the CDF (Cumulative Distribution Function) of the

(median) response time of the root servers and the ccTLD servers.

The third graph shows the hourly-average response time of the root

servers.

We are looking for volumteers to run the probe tools, especially from

developing countries.

If you can help, please send a note to kjc@wide.ad.jp.

ccTLD servers as reference points

The measured response time from a client site includes the latency of

the access link so that there is not much point in comparing the

response time from different measurement sites, especially when the

access link speed differs considerably.

One way to compensate for the access link speed is to use other

reference points, ideally, distributed around the world.

By comparing with reference points, we can obtain the relative

performance of the root servers.

This allows us to do measurement by dialing up to a commercial access

point in a target city where we do not have collaborators.

Although measurements may not be accurate due to long dialup delay and

a limited number of sampling count, we can get a rough idea about

the performance observed from those cities.

In our measurements, the ccTLD servers are used as reference points.

Most ccTLD zones have multiple servers; one or more in US and one or

more in their country or neighbor countries.

As a result, the majority of the ccTLD servers are in the Internet

core but the rest of the servers are distributed around the world.

From a given client site, the ccTLD servers are divided into 3 groups:

nearby servers, servers in the Internet core, and the rest of the

servers widely-distributed behind the Internet core.

Currently, there are 243 ccTLD zones which have 601 unique server addresses

in total.

We have manually investigated the locations of the ccTLD servers using

traceroute and the whois database, and found that

the servers are distributed in 154 countries.

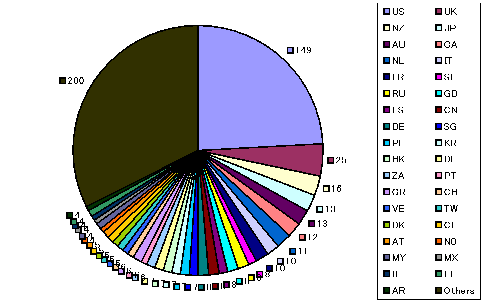

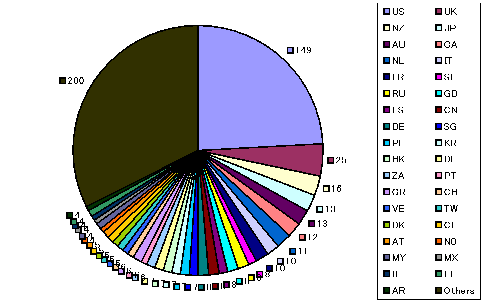

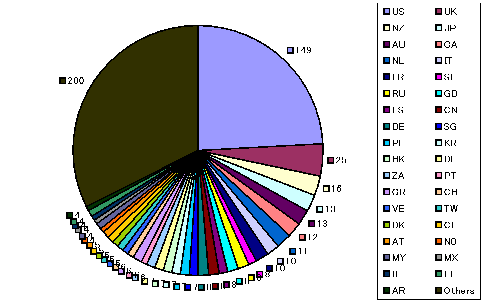

As Figure 1 shows, 149 servers (24.2%) are in US, 25 servers (4.1%)

are in UK but 200 servers (32.5%) in Others are distributed in 119

countries.

Figure 1. the distribution of the unique ccTLD servers

Note that the distribution of the ccTLD servers does not have any

meaning but we use it simply because the servers of the ccTLD zones

have wider distribution than those of other zones.

We currently measure the response time of all the ccTLD servers, but

it is also possible to select a subset of the servers so as to

represent different regions in the world.

Future Work

Our focus is the root server system but the techniques can also be

applied to other zones.

Developing a set of DNS measurement tools itself is a big challenge

since there are known difficulties in measuring DNS

[AL98,BkcN01,JSBM01,DOK92,KM01].

We intend to extend our research to more generic DNS measurement in

the future.

Related Papers

- Yuji Sekiya, Kenjiro Cho, Akira Kato, Ryuji Sonegawa,

Tatsuya Jinmei and Jun Murai.

Root and ccTLD DNS server observation from worldwide locations.

PAM2003, La Jolla, CA, April 2003.

(ps,

pdf).

- Ryuji Somegawa, Kenjiro Cho, Yuji Sekiya and Suguru Yamaguchi.

The Effects of Server Placement and Server Selection for Internet

Services.

IEICE Trans. on Commun. Vol.E86-B No.2. February 2003. p.542--551.

(ps,

pdf)

References

- [AL98]

- P. Albitz and C. Liu.

DNS and BIND (3rd ed).

O'Reilly and Associates, 1998.

- [BIN]

- BIND website at ISC.

http://www.isc.org/products/BIND/.

- [BkcN01]

- N. Brownlee, k. claffy, and E. Nemeth.

DNS damage.

draft paper, 2001.

- [DOK92]

- Peter~B. Danzig, Katia Obraczka, and Anant Kumar.

An analysis of wide-area name server traffic: A study of the domain

name system.

In SIGCOMM '92, pages 281--292, 1992.

- [JSBM01]

- Jaeyeon Jung, Emil Sit, Hari Balakrishnan, and Robert Morris.

DNS performance and the effectiveness of caching.

In ACM SIGCOMM Internet Measurement Workshop, November 2001.

- [KM01]

- Akira Kato and Jun Murai.

Operation of a root DNS server.

IEICE transactions on communications, E84-B(8):2033--2038,

August 2001.

- [MD88]

- Paul V. Mockapetris and Kevin J. Dunlap.

Development of the domain name system.

In SIGCOMM88, pages 123--133, 1988.

- [Moc87a]

- P. Mockapetris.

Domain names -- implementation and specification.

RFC1035, Internet Engineering Task Force, November 1987.

- [Moc87b]

- P. Mockapetris.

Domain names - concepts and facilities.

RFC1034, Internet Engineering Task Force, November 1987.

$Date: 2003/04/03 06:58:24 $